The Brahman's Star |

A Tale Of Kutb Minar |

Late one afternoon, a few centuries ago, a Brahman, who was toiling along the hot plain south of Delhi in North India, kept his eyes fixed upon the distant tower of Kutb Minar. This solitary tower was the only break in the wide stretch before him. Occasionally, the Brahman stopped to rest, leaning on his staff, but, even then, his eyes hardly glanced away from Kutb Minar.

"Nearer," once he muttered aloud; "nearer! I'll make it yet!" On he went, mile after mile, over the hot ground, leaving, far behind him, the magnificence of Delhi, where he had allowed himself to rest a very little while in the course of his long journey on foot from the north. He had the air of one making a pilgrimage -- of an iron-willed man who would let nothing come between him and his goal. No wind should check his gait, nor burning sun delay him. Never did soldier, merchant, or slave go on more steadily whether driven by his own will or by another's. One clear thought was in the Brahman's mind -- that if he didn't stop, he would reach Kutb Minar before nightfall. As he trudged along, he nodded complacently at the thought. Yes, this steady pace would certainly bring him to the tower before dark.

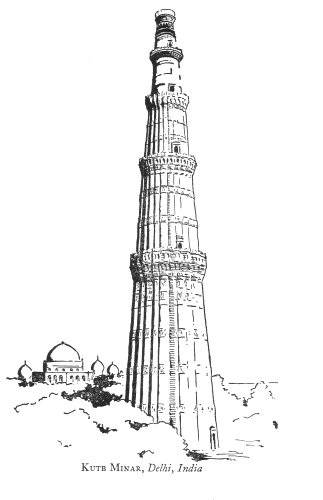

Now Kutb Minar was a good eleven miles from Delhi, and the Brahman was no longer young, but the growing nearness of the tower had added strength to him each hour, especially during the last mile. For some time, his eyes had been gladdened by the nearer view of the domes and minarets of the stately mosque, beside which the tower rose. At length, he began to see more clearly the tower itself, as it stood gleaming in the sunset light, a tapering shaft of sunset glory. For the modulated shades of sandstone -- purplish red at the base, pink in the second story, dark orange at the summit -- glowed in the yellow radiance of the setting sun with such dazzling reflection that anyone less wise than a Brahman would have found it hard to tell which light was of earth and which of the sky. The two upper stories, glistening with white marble, appeared to his eyes like the portal of heaven, concealing the mystery of all Hindu thought.

As the Brahman, absorbed in his meditations, slowly walked along, a tiger, limping, approached him. When the Brahman was aware of the tiger he stopped, not through fear, but sympathy.

"You have hurt your paw," he said, kindly.

"Sir," said the tiger deferentially, "if your heart prompts you to help me I will repay you at some future time in any way that I can."

"No payment do I want," replied the Brahman. "Let me see your paw!"

The tiger, sitting on his haunches, lifted his right forepaw from which a splinter of wood protruded. With deft fingers the Brahman extracted the bit, and, before the tiger could utter his thanks, said, smiling, "If your heart prompts you to help me and all mankind, see that the rest of your days and nights you make not too free use of that great strength given in the beginning to your ancestors and thereby to you. Remember you owe your life to man's kindness, because man's skill is ahead of all your strength. I must now go on my way."

"Sir," said the tiger, "I owe you great thanks, and I will remember." With that, he bounded away across the plain.

The Brahman plodded on with quicker steps to make up for the interruption. "Before the sun reaches that low cloud," he said to himself, "I shall be at the tower." And before the sun entered the cloud he was by the base of the tower. Standing near it for some moments, with bowed head and folded arms, he might have been a statue -- a statue with turban and robe that seemed a part of the sunset light.

Then he looked up with interest at the picturesque Arabic characters cut in the five dark bands around the lower stories. In the lowest band he saw five separate divisions of hieroglyphics, giving the titles of Kutab-ad-din -- the first of the shepherd kings of Delhi -- and Kutab's proclamation of himself as Sultan of all India; also, the name of Kutab's master, Muhammed Ghori, with words in praise of him. There were verses from the Koran, and an invocation to Visna Karma, "the celestial architect of the Hindus." Part of the higher inscription, too, the Brahman read: -- "Kutb Minar commenced in 1200 by the Amir, the Commander of the Army . . . of the Sultan Muhammed Ghori, to celebrate the great victory."

As the rest of the inscription was becoming hard to make out in the lessening light, the Brahman walked around to the door of the tower. Within the doorway sat a man weaving a small tapestry.

"Good-evening to you, O guardian of the Tower of Victory!" said the Brahman, pleasantly.

The doorkeeper, on seeing the Brahman, rose immediately with a word of greeting and added, "Sir, you arrive late in the day!"

"Day and night are one for me," answered the Brahman. "Have you many travelers, nowadays, to see the tower?"

"But few," said the doorkeeper. "You, sir, are the first for six days."

"A lonely life for you," remarked the Brahman. "No, sir," replied the man, quietly. "I have the sky both day and night."

The Brahman gave a keen glance at the doorkeeper's calm face, but made no comment. Taking a coin from his belt, he put it into the man's hand, and, with a look toward the west where the flaming sun was just now dropping below the horizon, he entered the doorway.

"I shall spend the night on the tower," he said, as he began to climb the stairs.

"A good night be yours, sir!" answered the guardian of the tower.

For a man no longer in his prime, the stairs were very many. Three hundred and seventy-eight steps at the end of an eleven mile walk from Delhi! Was the Brahman mad that he thought he could climb them? Old or young, mad or sane, up he climbed, stopping whenever his breath gave out, and improving those wasted moments by uttering prayers. Many a prayer there had to be during his climb, for, in truth, he went up more and more slowly. Not even a view from the tower did he have, for two excellent reasons: the stairway was dark, and he climbed with his eyes closed, just as the Indian saint of old climbed the mountain. Up, up, up, -- steps, pauses, prayers; up, up, up, -- more rests, more prayers, more steps, until, finally, the top!

Breathing heavily after his climb, the Brahman stepped out upon the narrow platform at the fifth story and looked westward. The brilliant clearness of the sky had already become dull and metallic-looking, except for a single, quivering star. He looked toward the northeast, in the direction of the lofty Himalayas, the overwhelming mountains that belonged, he knew, to the sky-dwellers -- their snow-covered tops always as billowy as ocean wave-crests. Presently he became absorbed in the majestic scene before him; the river Jamna, flowing slowly near Delhi, saffron in the twilight; the tomb of the ancient sultan, Altamsh, now a dark spot on the sand; the iron pillar -- that old East Indies pillar -- in the courtyard of the mosque. At a distance, he could make out the shadowy, blurred clumps of pomegranate and banyan trees, and could barely see the outlines of the temples of Delhi. Far beyond, he knew the mighty Ganges was forging along, ever protected by those sky-dwelling mountains. With folded arms he stood quietly for a long time, watching the light in the sky turn from copper color to deep bluish gray, until stars filled all space. Plain, rivers, mountain-tops vanished, but stars were overhead and all around -- multitudes of stars. The Brahman, with a whimsical smile, suddenly looked directly up to the very bright star over his head, and began talking softly.

"Mother Star," he said, in a happy voice, "I've come back. You know why. You know how my father brought me to the top of this tower when I was a boy, and told me your story. Mother Star, once, when you were sick, your two sons, the Sun and the Wind, and your daughter, the Moon, went to a feast. You lay on your couch, hour after hour. The elder son came home first. 'What have you brought me, Son?' you asked. 'Nothing, Mother,' answered the Sun; 'don't you suppose I wanted the good time for myself?'

"Soon the second son came in. 'Have you brought home anything for me, Son?' you asked. 'Nothing whatever, Mother,' the Wind replied; 'the feast was for the young.'

"Then the daughter came singing down a shaft of light. 'See, Mother,' she called out gaily, before you could speak; 'see what I have brought you -- fruits and sweet cakes!'

"She made you glad, Mother Star; the Moon-daughter made you glad. And as my father finished telling me the old tale he said to me, 'Son, you are a descendant of Mother Star, even as the king of Delhi was a descendant of the moon. When you are no longer young, come back to this tower if you have brought from the feast of life any blessings for others.'

"Mother Star, I am here. No one but you may ever know."

Taking, from an inner pouch, a pomegranate and a sweet cake, the Brahman laid them on the highest bit of ledge he could reach. Then he raised his hands toward the luminous star overhead. Presently, he let his hands drop, folded, upon his breast, and he stood almost as motionless as the star itself.

After a while, he sat down on the stone platform, and was lost in thought. He thought of King Bharata, that famous, early king of Delhi, who was descended from the moon; he thought of the tale of the Ganges -- how the river had been brought, as a maiden, to earth and had never regretted leaving her heavenly home. As he glanced in the direction of the Khyber Pass, he recalled the hordes of invaders who had come like strong winds into the land of India -- Greeks, Persians, Afghans, Tartars, savage chieftains -- always pushing on and on, while the stars, then as now, were serenely shining over the plain. Most of all, he thought of Mother Star, because the vivid remembrance of that night on the tower long ago, and the clear vision of the star, had possessed him throughout his long life. He had been a traveler in many lands and was a learned man besides. Many languages he knew, and under-stood the arts, astronomy, medicine, the winds that swept the ocean, and the talk of all animals and birds. Year after year, men in cities, and animals in the jungle, had sought his counsel. His life had been spent largely out of doors, so that he deeply revered the sun and the lightning, the mountains and the winds, and, especially, the cloudless sky and its presiding god, Indra. Yet, in his heart, from boyhood to manhood, he had always seen the star as he had seen it when his father told him the tale. Nothing on earth or in the sky had ever held for him such beauty, such reality, such inspiration, as Mother Star. To Mother Star he owed all that he was himself and all that he had brought to others. His offering, to-night, then, was more, far more, than a pomegranate and a sweet cake -- it contained the blessings for others which he had brought from the feast of life.

At dawn, an old Brahman was making his slow way across the plain toward Delhi. Behind him, the tower of Kutb Minar, catching the first rays of the sun, shone like a rainbow flame.

Suddenly a tiger bounded toward the Brahman and on reaching him said, "Sir, I owe you great thanks, and I have remembered all night." Then, together, the Brahman and the tiger walked toward the sunrise, talking agreeably as they went.

Sources And Further Reading |

Sacred Texts Tower Legends by Bertha Palmer Lane[1932]