The Country Bumpkin And The Hobgoblin |

A Folk Tale from Brittany |

Behind the town of Morlaix there is a beautiful glen which shelters many fine farms where cattle are bred and corn is grown. Here, long ago, one of the largest of these farms was tenanted by a good man whose name was Jalm. His only child, Barbaik, was a girl whose beauty was the boast of the countryside. Her face was lovely as a June rose, and her figure had all the charm of glowing youth and grace. And she was considered the best dancer and the daintiest heiress in all that broad country.

On Sundays, when she went to St. Mathew's church, she wore an embroidered cap, and a kerchief with large flowers on it. And she had five skirts, worn one above the other. Some of the old wives shook their heads as she went by and asked if she had sold the black hen to Old Nick and had thus gotten by uncanny means both beauty and fine clothes.

But Barbaik, who really was rather vain, cared nothing for what they said so long as she knew that she was the best dressed girl in the parish and the one after whom the lads ran. For that is what always happens. The hearts of young men are like wisps of straw hanging on a bush, and the beauty of maids is like the wind that carries them along in its train.

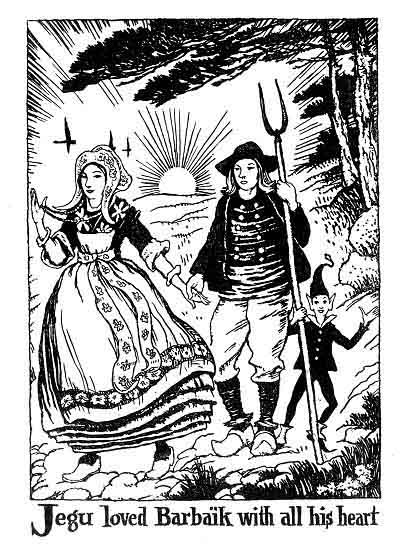

Among Barbaik's suitors there was one who loved her more than all the others. He was her father's farm hand, Jegu, a steadfast and upright Christian. But, alas, he was as rough as a Northerner and as ugly as a tailor. Barbaik would not listen to him in spite of all his merits. She always laughed and spoke of him as "the country bumpkin."

But Jegu loved her with all his heart. He bore all her insults and allowed himself to be badly treated by the girl who made joy and grief for him.

Now one evening as he was bringing his horses back from the pasture he stopped at a quiet pool to let them drink. He stood near the smaller horse, his head fallen on his breast. From time to time he would heave a sigh, for he was thinking of Barbaik. Suddenly a voice spoke to him, seemingly coming from the reeds that grew by the edge of the pool.

"Jegu, why are you grieving so?" the voice inquired. "You are not done for yet."

The ploughman was very much astonished you may be sure. He raised his head and looking about him asked, "Who are you?"

"I am the hobgoblin of the pool," the voice replied.

"But I cannot see you," replied Jegu.

"Look carefully into the reeds and you will see me," the voice answered. "I am disguised as a green frog. I can take any form I wish. And I can make myself invisible."

"Can you show yourself to me in the form that your race usually takes?" asked Jegu.

"I can if you wish," said the voice.

As it spoke a green frog hopped onto the back of one of the horses. It rested there a moment and then suddenly changed into a beautiful little gnome. He was dressed in apple green and was wearing shiny gaiters for all the world like a leather dealer.

Jegu felt some alarm and drew back a step or two. "Why are you afraid, Jegu?" said the green gnome with a smile. "I will not do you harm; on the contrary, I wish to help you."

"But why do you wish to help me?" asked the ploughman rather suspiciously.

"On account of a good turn you did me last winter," said the hobgoblin. "Did you know that the elves of the white corn country declared war on our race?" continued the hobgoblin. "They accused us of helping mankind. And we were obliged to turn ourselves into animals in order to hide. Since then we often take these forms to amuse ourselves. That is how I came to know you last winter."

"How was that?" asked Jegu.

"Do you remember one day when you were ploughing the alder-field you found a poor little redbreast caught in a snare?" asked the hobgoblin.

"Yes," answered Jegu, "and I even remember what I said: it was 'You do not eat the corn of Christian folk, so take your flight, bird of Heaven.'"

"Well I was that bird!" the hobgoblin continued. "And at that time I swore to be your friend. And I am going to prove it to you now by helping you to marry Barbaik."

"Oh, dear little hobgoblin, if you succeed in doing that I shall never refuse you anything, except my soul!" Jegu replied eagerly.

"Let us arrange it all," the gnome said, "and in a few months' time you will be the master of the farm and the husband of Barbaik."

"And how will you manage that?" asked the youth.

"You will know that later on," replied the hobgoblin. "Go on smoking your pipe; eat, drink, and do not worry."

Jegu said that would be easy enough and that he could obey the pixie's orders. Then Jegu thanked the little green man and took off his bat just as he did to the mayor or the priest. After which he led his horses home.

The next day was Sunday, but Barbaik got up at the usual early hour, for it was her duty to look after the stables.

Imagine her surprise when she found that some one had already filled the mangers and milked the cows. She remembered that she had said, on the evening before to Jegu, that she wanted to be ready so as to go to a dance at the Pardon of St. Nicolas. So, when she found the cows milked and the mangers filled, she thought it was Jegu who had done it, and she thanked him. He answered gruffly that he did not know what she meant, but the way he said it made her think all the more it had been be who had done the work.

After that some kind turn was done for her every day. Never had the stable been so clean nor the cows so plump. Every morning and evening Barbaik found her jars full of milk, and a pound of butter freshly churned and decorated with a blackberry leaf lying on the table. This meant that now she did not have to get up till broad daylight, just in time to tidy up the house and get the breakfast.

Sometimes even this work was done for her. One morning when she arose she found the house swept and clean, the furniture polished, the soup boiling on the fire, and the bread cut up and put in the bowls; so that all she had to do was to walk as far as the barn door and call the men in from the field.

She imagined it was a kind attention of Jegu's, and she could not help thinking that he would be a very convenient husband for a woman fond of taking things easy, even if he were a country bumpkin.

In fact the heiress had only to express a wish in Jegu's hearing and it would be fulfilled at once. If the wind were too cold or the sun too hot and she was afraid of spoiling her complexion, she would say, "I should like to see my churn clean and in its place, and my water jugs full of fresh water and covered with fresh linen." Then she would go off to have a chat with her neighbor and when she came back there would be her churns and water jugs standing on the cool flag just as she wished them.

If the rye bread were too heavy to knead, and the oven slow in heating she had only to murmur, "Oh! I wish my fifteen pound loaves were in a row on the bread shelf!" and behold! when next she came into the kitchen, the loaves would be ready for her, beautifully baked.

Again, if the market seemed too far away, and the road so full of ruts that driving was hard, she had only to say the evening before so that Jegu could hear her, "If I were only back home from Morlaix with my milk jar empty, my butter dish in the bottom of it, a pound of ripe cherries on the wooden plate and a silver piece in my apron pocket!" Next morning she would get up and find the empty milk jar with the butter dish in the bottom of it, the pound of ripe cherries on the wooden plate, and a glittering silver piece in her apron pocket.

These happenings did not stop here. For if she wanted to send word to another girl to go with her to Morlaix to buy a few yards of ribbon, or if she wanted to know at what time the procession was to set out from the church she had only to say the word and it would happen at once. And it seemed always to be Jegu who was the cause of it.

So she began to imagine that she could not live without the country bumpkin. She needed him for work and for play; he was her faithful dog and her guardian angel, she thought.

At last the hobgoblin advised Jegu to ask for her hand and this time Barbaik gave heed to his wooing. She thought him far from handsome, and clumsy as a lover, but as a husband he would do very well. He would manage all the work and she could sleep late as did the town lady, and wear fine clothes and spend her time on her neighbor's doorstep with her hands folded in her lap. And she would continue to dance at all the Pardons. She imagined that Jegu would be like the horse obliged to drag the cart, while she would be the proud driver perched high on her bundle of bay, making her nag jog along to the flick of her whip. So while Jegu talked she pictured to herself the rosy future. Then she answered him as a well-brought-up heiress is bound to make answer to her suitor. She said she would do as her father wished. But she knew that Jalm would consent, for her father had said more than once that Jegu would make a fine manager for the farm.

So, in the course of the next month, they were married. It seemed as though the old farmer were only waiting for that event before taking his leave of this world, for he died a few days after the wedding, leaving the farm to the young couple.

It was a heavy burden for Jegu, but the good little hobgoblin came to his assistance. The gnome did the ploughing, and he accomplished as much work as four ordinary hired men. It was the gnome who kept the tools and the harness in repair, and he always told Jegu the best time for sowing the grain and for the reaping.

If Jegu had any work that must be finished at once the little green gnome would quickly bring his friends to help. All the pixies would come either with pitchforks, or hoes, or reaping-hooks on their shoulders, and the work would be done in no time.

When Jegu was short of horses the hobgoblin would tell him to go to one of the pixie towns out on the heath and to say, "Little friends, lend me a team of horses and everything they need for ploughing," and the team would appear in less time than takes the telling.

And, most surprising of all, the hobgoblin of the pool asked in payment for all these deeds only as much pudding each day as would fill the old dipper.

Jegu was grateful to the hobgoblin and loved him as his own son. But Barbaik hated the gaitered imp. She had her own reasons for that. For beginning the very day after her marriage, to her astonishment, no one helped her any longer with her work. And when she complained to Jegu about it he did not seem to understand her.

But the gnome, who was near, overheard her lament and burst out laughing. He then confessed to her with grins that he had done all the kind deeds in order to make her agree to marry Jegu. Now, however, he said he had other things to busy him and she would have to look after the house herself.

So disappointed and surprised was Jalm's daughter that she was filled with awful wrath against the hobgoblin. How dared the creature treat her thus?

Every morning now Barbaik had to get up before the sun to milk her cows or go to market. And evenings up she had to sit till midnight churning butter. She was embittered with the imp who had deceived her and had led her to look forward to an idle, care-free life. And she waxed yet angrier and angrier when she gazed on poor Jegu's red face, squinting eyes, and coarse hair.

"No, no, wicked elf," she vowed to herself, "never will I forgive you for having made me marry a country bumpkin! But for you I should still be the heiress, courted by the lads. I should still go to dances and all my suitors would bring me cherries, hazelnuts and the good things of the seas, and I should hear them tell me that I am the prettiest girl in all the countryside. But now I must accept nothing save from my clumsy husband. I must please only him! O wicked, spiteful elf!"

Yet wonder of wonders! One day the gnome did offer to help her. She was invited to a wedding and as all the horses of the farm were ploughing in the fields she asked the hobgoblin for a steed. He told her to go to the pixies' town and ask for exactly what she wanted.

So Barbaik went to the pixies' town on the heath and thinking that she was asking properly, she said, "Little elves, little elves, lend me a black horse, with eyes, mouth and ears, and with a bridle and a saddle."

No sooner asked than granted. The horse she wished stood instantly before her. She mounted him and set out for the wedding. But soon she began to notice that everyone laughed as she passed by.

"Look, look," cried each. one to his neighbor, "the farmer's wife has sold her horse's tail!"

Barbaik looked around quickly, and sure enough, her horse had no tail! She had forgotten to mention one when she told the pixies what she wished. They had taken her at her word and had given her just what she had asked for.

Barbaik was sorely vexed and tried to ride on quickly, but the horse would not go faster, and she had to put up with all the jokes of the passers-by.

By the time she reached home that evening, instead of being grateful for the pixies' generosity, she was angrier than ever with the little man in green. She accused him of having played a crafty trick upon her. She made up her mind to punish him.

It was not long before spring came. Now spring is the birthday time of all gnomes, elves, and fairies, and the little hobgoblin asked Jegu if he might be permitted to invite his friends, the other little hobgoblins, to come and spend the night in the hospitable barn, for he wanted to give them supper and a dance. Of course Jegu could not refuse the gnome this pleasure, so he asked Barbaik to put her best tablecloth on the barn floor, and to serve buttered rolls, all the day's milk, and as many pancakes as she could make in one morning.

To Jegu's surprise Barbaik did not object. She made the pancakes, prepared the milk and baked the rolls and then, at nightfall, took them to the barn and arranged them for the goblins' feast.

But she did something else that Jegu had not asked for. She put the red hot cinders she had just taken from the fire all around the tablecloth in the places where the pixies would sit down. So when the hobgoblin and his friends arrived for the merrymaking they sat on the hot coals and burned themselves most painfully. Up they all jumped and fled with shrill cries of dismay and pain.

But in a twinkling they were back with jugs of water and after having put out the fiery coals they began dancing around the barn singing in angry voices:

Has played on us a horrid trick,

So from the country we shall flee

And leave her to her misery.

And they vanished from the farm that very evening, never to return.

From that night forward Jegu and Barbaik had all the labor of the farm to do themselves for there were no kind elves to help them, nor to bring their wishes true. But some folks said Jegu still had ten pixies to work for him, pixies that were not invisible: his eight fingers and his two thumbs!

Sources And Further Reading |

Sacred Texts Folk Tales of Brittany by Elsie Masson [1929]